On 19 September the chief executive of the Law Society, Catherine Dixon, delivered a keynote address at the International Bar Association conference in Washington DC.

The work of the Law Society of England and Wales

The Law Society is the professional body that represents more than 170,000 solicitors in England and Wales.

Our vision is to be valued and trusted as a vital partner to represent, promote and support solicitors while upholding the rule of law, legal independence, ethical values and the principle of justice for all.

Last year we launched our new strategy which sets out our three aims:

- representing solicitors: we represent solicitors by speaking out for justice and on legal issues

- promoting solicitors: we promote the value of using a solicitor - at home and abroad, and

- supporting solicitors: we support solicitors to develop their expertise and their businesses, whether they work in firms, in-house or for themselves. This includes working to ensure that the best candidates can join the profession - irrespective of their background and supporting equality, diversity and inclusion in the solicitor profession.

We also fulfil an important public interest function which aims to ensure access to justice, protect human rights and freedoms and uphold the rule of law.

The future of legal services

As part of our work to develop our strategy, we published a piece of research to identify what the future will bring for the legal profession.

The main finding of this research is that solicitors face a future of change. These changes are dynamic and happening at an unprecedented scale and speed. These drivers of change are:

- economic change and increasing globalisation

- technological change including Artificial Intelligence (AI)

- increased competition

- changes in buyer behaviour

- wider policy agendas

This session will focus on technology and innovation as a driver of change. For more information see our report

The Future of Legal Services.

Technology and innovation

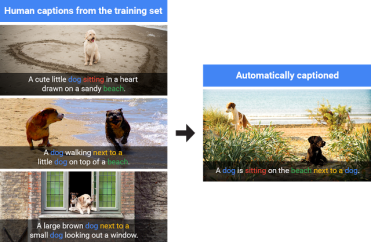

New forms of technology are having an impact on the way we practice law, our firms' workforce, skills and talent and our business models. Our research showed that technology is:

- enabling lawyers to become more efficient at some procedural work which can be commoditised

- reducing costs by using technology - including artificial intelligence systems

- supporting changes to client purchasing decision-making

I will briefly refer to each of these aspects.

Driving efficiencies in legal practice

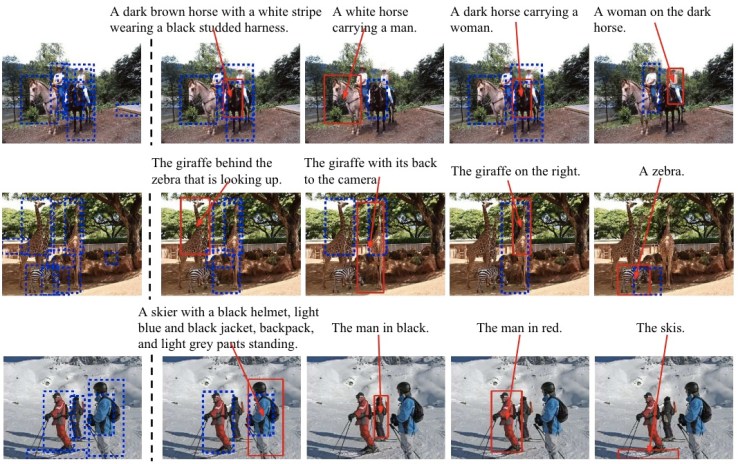

In the past decade we have seen an increase in the use of machine learning and artificial intelligence in firms. For example:

- KIRA is a software tool for identifying relevant information from contracts. It has a pre-built machine learning model for common contract review tasks such as due diligence and general commercial compliance.

- IBM Watson: many firms have improved the way they conduct legal research by using systems like Watson that uses natural language processing and machine learning to gain insights from large amounts of unstructured data. It provides citations and suggests topical reading from a variety of sources more quickly and comprehensively than ever before leading to better advice and faster problem solving.

- Luminance software: The firm Slaughter and May announced last week that it has been testing software on merger and acquisition matters. The programme aims to automatically read and understand hundreds of pages of detailed and complex legal documents every minute.

- Technology-assisted review (TAR) - ThoughtRiver: This mechanism is used in litigation for electronic disclosure (or discovery) in many jurisdictions including the US, Ireland and England and Wales. In the US it has been used since 2012, in Ireland since 2015, but in the UK its use was only accepted by the courts this year. In the case of Pyrrho Investments Ltd and another v MWB Property Ltd, the High Court accepted the use of predictive coding in electronic disclosure for the first time. Master Matthews listed a number of reasons that predictive coding was beneficial and found 'no factors of any weight pointing in the opposite direction'. One of the benefits he highlighted was that 'there will be greater consistency in using the computer to apply the approach of a senior lawyer towards the initial sample (as refined) to the whole document set, than in using dozens, perhaps hundreds, of lower-grade fee-earners, each seeking independently to apply the relevant criteria in relation to individual document.'

Therefore, technology can play a facilitative role in helping law firms achieve productivity-driven growth by increasing accuracy, saving time and driving efficiencies. This has been the case in larger firms that provide business to business services.

The use and offer of these tools and services is increasing. Legal technology companies are one of the biggest new groups of players mixing up the dynamics of the market - for example, next month the Law Society is co-hosting an event with Thompson Reuters, Freshfields and Legal Geek aimed at legal technology start-ups to promote innovative solutions for firms and in-house lawyers.

The courts are also embracing technology. In England and Wales they are starting to move away from paper based systems towards online - albeit slowly! The Lord Chief Justice's report to parliament indicated that: 'outdated IT systems severely impede the delivery of justice.' In response, hundreds of millions of pounds have been allocated for the modernisation of IT in courts and tribunals and to modernise their procedures.

As part of this modernisation programme, proposals have been put forward for an online court for claims up to £25,000. Although the Law Society fully supports the need for the judiciary to have fully functional IT systems, there are concerns that will need to be addressed to ensure access to justice is maintained.

Reducing costs - job automation and workforce

Concerns have been raised about job automation in the legal services sector. Research by Deloitte, for example, on the effects on technology on the profession in England and Wales suggests that about 114,000 jobs are likely to become automated in the next 20 years. Leading academics such as Remus and Levy (2015) and McKinsey (2015), are also predicting between 13 per cent and 23 per cent of automation in legal work - mainly for routine and procedural work.

However, projections by the Warwick Institute for Employment Research, estimate that 25,000 extra workers will be needed in the legal activities sector between 2015 and 2020. So, the evidence is inconclusive - the picture is much more complex than the media headlines suggest.

Technological change, right from the industrial revolution, has raised questions that jobs would be decimated. And while some jobs were eliminated following the introduction of machinery, new types of jobs were created.

We are experiencing the same phenomenon today and we believe that the profession will continue to learn, to evolve and to reinvent itself - as we have done so far.

It is expected that the push towards automation of routine work will be levelling off by 2020, and instead we might expect to see technology fuelling innovative models of delivery or service solutions.

There will be an impact on strategic workforce planning. Specifically, human resources departments and learning and development teams need to:

- Identify the skills, knowledge and aptitudes that are needed for new lawyers. For example, junior lawyers are being encouraged by firms and prospective employers to hone skills on social media, marketing, business management and even coding in addition to their technical abilities and knowledge.

- Support mid-career lawyers to rethink their development and progression in the firm to ensure that they are prepared for the future.

- Think about the future of legal practice - some academics, such as Professor Richard Susskind have mooted the idea that the future of law firms and legal practice could be in the hands of other professionals or some hybrid species of 'lawyer-software engineer'.

Changes to client purchasing decision-making

Technology is also having an effect on legal consumer buying behaviours. To remain competitive, firms are increasing their online presence enabling them to interact with clients online.

Law firms, advice agencies and non-profit organisations have made great strides in the development and use of web-based delivery models, including websites with interactive resources, smart forms and general information aimed at existing and potential clients.

Some examples are:

- The Solution Explorer: This is the first step in the British Columbia Civil Resolution Tribunal. The goal is to make expert knowledge available to everyone through the internet using a smart questionnaire interface process aimed at individuals with small claims or condominium disputes. This interactive tool will be available online, 24 hours a day, seven days a week. The tool is in an online beta test as of June 2016.

- Online platform Rechtwijzer [Reshtwaiser] (Roadmap to Justice): It has been available in the Netherlands since 2007 for couples who are separating or divorcing. It handles about 700 divorces yearly and is expanding to cover landlord-tenant and employment disputes. At first, Dutch lawyers were wary of the platform as they feared a loss of billable hours, but now many view it as an efficient way to process simpler cases, leaving lawyers to focus their expertise on more complicated matters.

- CourtNav: An online tool developed by the Royal Courts of Justice in England and Wales in partnership with Freshfields. It helps individuals complete and file a divorce petition.

- Do-not pay - an AI system challenging parking tickets: It was reported that a 'chatbot lawyer' overturned 160,000 parking tickets in London and New York. The programme was created by a 19-year-old student at Stanford University, and works by helping users contest parking tickets in an-easy to-use chat-like interface. The programme identifies whether an appeal is possible through a series of simple questions - such as were there clearly visible parking signs - and then guides users through the appeals process.

The majority of these web-based models are being tested or have just started to be implemented, therefore their success has not yet been fully proven. However, the 'do-not pay' parking programme has taken on 250,000 cases and won 160,000, giving it a success rate of 64 per cent..

What will the future bring?

Based on this data, the following facts have been identified:

- The legal market is embracing the use of artificial intelligence in their work. This is the case in firms and in-house.

- Research published earlier this month shows that 'the major law firms that publicly acknowledge making use of artificial intelligence (AI)-driven systems is now at least 22':

- nine based in the US

- nine based in the UK

- one based in Europe

- two based in Canada

- one with international headquarters (Dentons)

This number could be higher as there may be firms that use this type of technology but have not made it public, and others may still be in a testing and pilot phase.

The types of firms taking up AI are mostly large commercial firms but there are also some medium-sized firms such as Dentons, DLA Piper, Reed Smith, Clifford Chance, Macfarlanes and Davies (in Canada). This research suggested that the level of adoption of AI shows that 'we have now moved beyond the 'early adopter' phase and are seeing a broader use of the technology.'

Leading academics and commentators have also said that there are some emerging trends:

- Machine learning is a top strategic trend for 2016 (Gartner).

- AI will be a necessary element for data preparation and predictive analysis in businesses moving forward (Ovum).

- There will be a market for algorithms as businesses learn that they can purchase algorithms rather than programme them from scratch (Forrester).

- The impact of technology is being felt where firms largely service mass or process-driven needs rather than specialist cases.

- Technological innovation has led to more standardised solutions for the delivery of legal processes and the ability to commoditise many legal services.

However, some clients remain sceptical about the ability of technology to do a better job at legal service delivery than an actual lawyer. While they accept technology as part of assisted document review, some do not yet fully trust technology to analyse a legal situation or offer legal options. Whilst we expect to see some shift in this attitude by 2020, the human-to-human relationship will still be favoured by many large corporations.

Many clients (including in-house lawyers) still rely on major law firms (Top 200, City, Magic Circle) for their complex and specialised legal issues and are willing to pay the higher premium for these, despite the fact that technological solutions are available to address some of these complex legal issues at a much lower cost and with greater accuracy. We need to separate specialist advice from commoditisation.

Conclusion

To conclude, I want to reiterate that change is driven by:

- economic change and increasing globalisation

- technological change (including Artificial Intelligence- AI)

- increased competition

- changes in buyer behaviour

- wider policy agendas

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz said in the 17th century that 'It is unworthy of excellent men to lose hours like slaves in the labour of calculation which could safely be relegated to anyone else if machines were used.' Now that excellent types of technology, machine learning and artificial intelligence are available, we should embrace it and build on it to deliver better services.