Sci-Fi movies have long played on our fear of artificially intelligent robot armies taking over the world, but hidden and often secret algorithms are already busy at work in society, delivering sometimes life-changing consequences.

Humanoid robots, capable of thinking, moving and talking, is the most common imagery when it comes to Artificial Intelligence, but incredibly powerful computer algorithms, which silently churn through oceans of data, also fall under the AI umbrella.

Computers are already making important decisions and influential judgements in the key societal pillars of justice, policing, employment and finance.

NSW Police are known to be using a controversial algorithm which claims to predict youth crime before it happens. But critics of NSW Police's Suspect Target Management Plan (STMP) system argue the software is racist, and unfairly blacklists and targets Aboriginal youths.

In the US an algorithm used by judges to assist parole and bail decisions has also been accused of race-bias against black defendants.

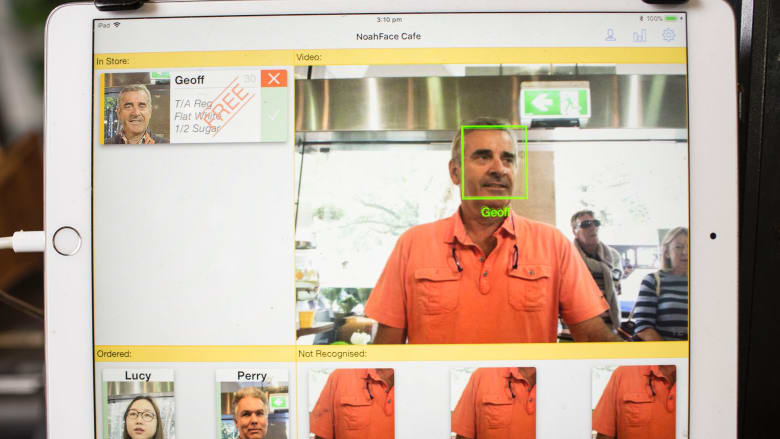

Facial recognition software is now helping recruitment firms decide job postings and if a candidate's facial movements reveal the desired levels of trust, confidence and an ability to cope under pressure.

Algorithms and big data will go way beyond your subconscious facial tics to try and assist companies and officialdom learn more about you and your personality, and predict your behaviours.

Spelling mistakes in your emails, and the time of day you send those emails, can be harvested by highly complex algorithms to assess whether you can be trusted to repay a bank loan or not.

Ellen Broad, an Australian data expert and specialist in AI ethics, believes the biggest concern about the relentless rise of the algorithm is transparency.

Speaking to nine.com.au, Broad said many of the algorithms which make potentially life-altering decisions are developed by private companies who will fight tooth and nail to keep their proprietary software top secret.

The problem with that, Broad says, is people should have the right to know how and why these tightly guarded algorithms make a decision.

Private companies armed with trade secret algorithms are increasingly enmeshed in public institutions whose inner-workings have traditionally always been open to scrutiny by media and society.

A computer program called Compas, operating in the US justice system, recently became a lightning rod over this issue.

Designed to help judges assess bail applications, Compas drew fierce criticism after an investigation by Pro Publica in 2016 claimed the algorithm was racist and generated negative outcomes for black defendants.

Northpointe Inc, the company which built Compas, rejected the report but refused to divulge what datasets the algorithm analysed, or how it calculated if a judge should deem someone was a reoffending risk.

"One of the key criticisms of Compas was this is a software tool being used to make decisions that affects a person's life," Broad said.

Ellen Broad is an independent data consultant who wrote the book, Made by Humans: The AI Condition. (Supplied) ()

"Our justice system is built on principles like you have a right to know the charges against you, to know the evidence that will be laid out in relation to those charges, and you need the opportunity to challenge and present your own evidence.

"Compas uses hundreds of variables and you don't know how it works."

Northpointe said its algorithm had learned from a large dataset of convicted criminals to make predictions about who was likely to reoffend.

The Pro Publica investigation alleged the Compas program was found to over-predict black defendants as being likely to reoffend, and under-predict on white defendants.

NSW Police have run into similar accusations of racial bias with its STMP software, an intelligence-based risk assessment program that aims to prevent crime by targeting recidivist offenders.

Research led by UNSW in 2017 said STMP generated a kind of secret police blacklist which disproportionately singled out youth under the age of 25 and Aboriginal people.

The report said people, some as young as 13, were being repeatedly detained and searched while going about their everyday lives, and being visited at home at all hours of the day.

UNSW researchers said NSW Police would not divulge the inner workings of STMP. Nine.com.au contacted NSW Police for comment for this story, but have not received a response.

"We need to know how accurate these systems are before we allow programs to make highly important decisions for us," Broad said.

A computer algorithm called Security Risk Assessment Tool is used in Australian immigration detention centres to assess the security risk of asylum seekers, criminals and overstayers.

Because algorithms learn from the data humans feed it, there is a real risk of automating the exact cultural biases these programs are supposed to eliminate, Broad says.

"If there are structural inequalities in your underlying data, and unfair trends in real-world demographics and behaviours, there is only so much a machine can do."

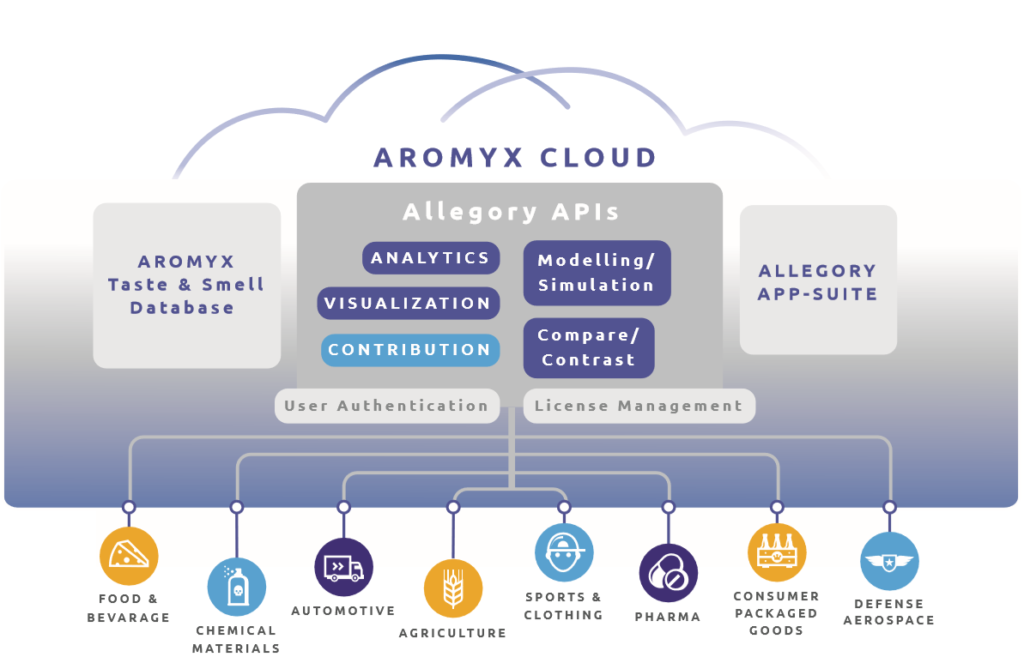

Australian company Lodex is just one of many start-ups which have developed algorithms that can trawl through people's social media and email accounts to make predictive decisions.

Lodex founder Michael Phillipou told nine.com.au his company's algorithm analyses 12,000 "data points" to calculate credit scores that help banks and lenders decide if a customer will default on a loan.

Accurate credit scoring is all about data, Phillipou says.

Phillipou says someone's email inbox and the way they operate their email account are important factors in the Lodex algorithm.

If given access by loan applicants, Lodex will make judgements on your character and financial risk based on grammar and spelling mistakes in your emails, how long it takes you to reply to an email, what time of day you send mail and if you populate a subject field.

"If someone is not very timely in the way they respond, it provides an indication of something," Phillipou says.

"If someone is very active between the hours of 1am to 4am, it indicates something.

"Because of the proliferation of information available, be it on people's mobile phones, their laptops or social media, we can build highly predictive models," Phillipou says.

Phillipou says digital footprint data, which is used to create a "social score", is currently used to complement robust information held by traditional credit bureaus.

However, Phillipou forecasts digital footprint data is set to become more and more important – and influential - to banks and lending institutions.

Since launch in late 2017, Phillipou says more $400m in loan auctions have been run on the Lodex app.

Broad, author of a book which explores our increasing reliance on AI, Made By Humans, is wary of companies using endless pools of data to make specific, targeted decisions.

She acknowledges a link could exist between spelling errors in emails and defaulting on a financial loan, but Broad warns: "That is not causation".

"Sometimes the more we try to use a dataset that is unrelated to the thing we are actually trying to measure the more risk we have of introducing noise or making [far-reaching] correlations."

Algorithms that can decide our liberty, shape our career prospects or bolster our financial security will only become more prevalent in the future.

Against that backdrop, one of the biggest AI questions we should be asking, Broad says, is what kind of Artificial Intelligence do we want making decisions?

"AI can't necessarily offer us a better and fairer future," she says.

One thing Artificial Intelligence is very good at, Broad says, is helping humans quantify and understand if our systems and institutions are biased.

Garbage In, Garbage Out is an old maxim in the computing world, expressing the idea that poor quality input will result in poor quality output.

Broad says ensuring and increasing the transparency of algorithms will be vital for modern society.